We all wish for that magical night we get called onto stage to spontaneously perform the lead role. Musical Theatre Appreciation Society's Dawn Bush wonders if being an understudy is just the same thing...

It’s the stuff that theatrical dreams are made of. The star of the show can’t go on, and an audience member cries “I know the role!” She goes on, performs with jaw-dropping brilliance, and becomes an overnight star.

For one girl in January 2016, Melissa Bayern, that dream looked like becoming a reality. It happened at a performance of Into the Woods at the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester - and such things are indeed what dreams are made of. The Stage reported the incident with the headline:

“Audience Member Covers for Performer after Last Minute Illness.”

Melissa Bayern in costume backstage at the Royal Exchange, Manchester, as the Witch in Into the Woods

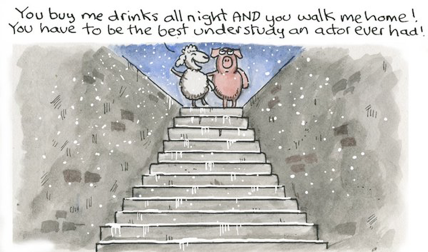

When pondering the role of understudies (beautifully covered by Dries Janssens in his blog), my interest was piqued exactly because of the dream-like quality of the story, which I was sure wasn’t all it appeared to be. Does it suggest that just anybody (even a random audience member) can understudy a role if they know the words? They don’t even have to perform that often.

Isn’t being an understudy the easiest job in the world? Couldn’t anyone do it?

There is no doubt in my mind that such a substitution would cause problems. An audience member might know the songs and even the lines if they’ve seen it over and over, but there is far more to understudying a role than simply knowing the words. Blocking; timings; costume; (does it fit? Are there any quick changes?); even the music (is it in the right key?). There is often notoriously little room backstage so how did she know where to be - did the other actors spend their time pushing her about? Understudies have to be physically and mentally ready to go on at a moment’s notice. Did she have time to warm up? What about the relationship with the rest of the cast?

How on earth did they cope?

Some years ago, I saw a performance of The Taming of the Shrew at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, starring comedienne Josie Lawrence as Beatrice - a brilliant performance from all concerned. I remember noting with amusement that the young man playing one of the servants must be quite tall, as the trousers he was wearing did not meet his shoes by about ten centimetres. It seemed odd, but part of the character’s comic nature. It wasn’t until the end of the performance that I twigged. The palpable sense of relief from the cast indicated that the very young man had stepped in at the last minute to understudy the role. But, it didn’t make any difference to my enjoyment of the performance.

The point I’m making is that the substitution of one person for another – particularly in musical theatre, where the skills required are broader than in straight plays and are known as triple threat (acting, singing, dancing) – is a much bigger deal. Ok, so a poor performance isn’t exactly life-threatening, but it really galls me when people think that, if they’re not getting a star name, they’re getting someone that is somehow less. Less prepared? No. Less rehearsed? On the contrary. Less skilled? Probably not - in fact in some cases, the understudy might have more experience in musical theatre than the soap or pop star brought in originally as the crowd-puller.

In the notorious case of lead Sheridan Smith and understudy Natasha Barnes in Funny Girl, many people were more than satisfied with Barnes' performance - I have one friend in particular who would have preferred to see Natasha Barnes, as the unpredictable nature of Smith’s performance on the nigh made her feel quite uncomfortable. This is not to underestimate Smith’s skill, but actors are sometimes too ill to perform and public or private pressure shouldn’t make them feel they must appear. Barnes is now a West End star in her own right, simply because she did her job well, utilising all her training, skill and experience.

There was a recent outcry on Twitter, when the Delfont Mackintosh group forbade their understudies to tweet when they were going to be appearing. Now, given the behaviour of many audience members, I can understand that such tweeting might cause a whole host of administrative problems. If it gets out that a star is not performing, the audience will often want to book an alternative performance, or change the tickets if they’re already bought. The situation is further exacerbated by the differing terms and conditions of Broadway vs. the West End; on Broadway, the audience is deemed to have paid to see the star, and is given a refund or replacement without question. However in the West End, although many productions are understanding and will at least exchange your ticket for another date, they are not legally obliged to do so - you have paid to see the show, not the star.

The reason for forbidding understudies to tweet their performance dates is likely to be due to the sad fact the house will not be as full. However, I think it very dubious that the Delfont Mackintosh group felt it necessary to clip their understudies’ wings in this way. They don’t get to perform on a regular basis, of course they want their family and friends, as well as industry professionals, to have the opportunity to see them in action.

I know that most wouldn’t consider asking for money back if the star wasn’t appearing, but I wish this attitude extended to audiences everywhere. I understand that if you’ve paid a lot of money to see a particular person, there is going to be a certain amount of disappointment.

But surely it’s better to see an excellent, healthy understudy than an unwell star who will give a second-rate performance?

Back to the Melissa Bayern story - I am not surprised to find that, although it’s undoubtedly the fairy-tale that many performers dream of, it is of course backed up by Melissa’s 3 years of hard work at the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama, the fact that she’d only just performed the role in her final year showcase and her willingness to spend 5 hours rehearsing at short notice. She had costume fittings and dance rehearsal, eventuall playing the role for 7 nights with lots of help from the cast, including them telling her when her next entrance was and where she needed to be. The clue is in the detail – the kudos that goes to the cast, who were “incredibly adaptive and supportive.” Whatever her skill level, it had to be better for the cast to have her, a relative novice, than the person who was trying to perform with script in hand. Good for her – but not, I’m sure you’ll agree, an ideal situation.

So if you are one of those that think understudies are akin to an audience member stepping in, read the blog from Dries that I mentioned earlier. Any doubts you might have about the skill required in understudying a role will be put to rest - you will certainly think twice about crying out “I know the role!” should the star, the understudy and all the swings be sick at the same time. ![]()